Ansel Adams, Part II

Packing 3 quarts of water, I thought that would be enough to get me up there and back down. I also envisioned that I would be back at my car at maybe 7 PM. Boy, was I wrong, wrong, wrong! Even though I was approaching 6000 feet in elevation, the temperature was very, very high. I knew I would be rationing my water, to insure that I would make it to the top and then back down again. However, I started to sweat very profusely and decided I needed to ration my SWEAT! I chose to sit and take more breaks when I would start to sweat too much. This became a somewhat of a mindgame, and I started to question whether I should continue up through the thick brush, which was taking a lot out of me, and also making my ascent not a very direct one, afterall.

My destination was tantalizingly close but, being so out of shape and dehydrated was definitely having an effect. I also had no idea of what time it was. Luckily, I emerged out of the brush, and into a year old lightning fire where it was much more open. The loose decomposed granite was hindering me, as well, causing me to plod along with tiny strides, to keep from breaking traction and wearing myself out further. I paused in the shade of a jeffrey pine to load my other digital card into my camera and take a final breather before the final stretch of the steeper granite slabs of the "Diving Board", as it's called on the topographic maps. I did have a little idea of what I would see at the edge but, I was truly awestruck by the abruptness and contrast of this amazing geologic feature.

I left my feet and found a secure place to crouch, then began to take it all in. Just how could I do this place justice with such a limited time and only 17 frames of digital space left on my camera? Too many of the pictures I took I wasn't really satisfied with. I didn't have the time or the energy (or space) to seek out the best shots.

I knew that I HAD to shoot the view looking down on Mirror Lake, shown in the picture below. The above picture I also knew I had to take, even though it was looking into the sun. Even my wide angle lens couldn't quite get enough of the scenery into the frame. I wonder what the focal length Ansel Adams used that day.

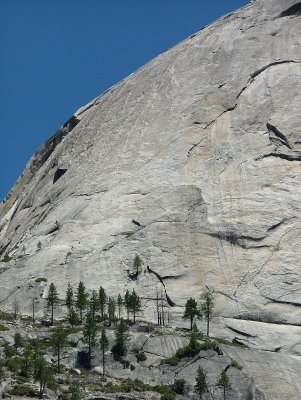

This next picture below is what most closely resembles that picture Ansel Adams took with his very last frame. I tend to think that he took his picture near that closest pine tree in my picture. The face of Half Dome is so much more intimidating up close and personal. However, the jutting overhangs of the "Diving Board" were overwhelming. Pictures just do NOT do it justice. I quickly used up the last of my frames and didn't want to linger up there in the hot sun.

I knew that the descent would be an epic adventure in itself, as I would have to make a huge decision about which route to use for the descent. I did see some rock "cairns" (stacked rocks marking the route) on the way up and hoped that they would lead me to an easier descent than the thrash-fest I experienced on the way up. Unfortunately, this marked route was only for people ascending to the famous "Snake Dike" climbing route, the second easiest way to get to the top of Half Dome. (There was one party of three climbing that route, and I had much pity for them, with no shade and somehow carrying all the water they would need for the rest of the day).

As I descended, it was VERY hard to follow these cairns, and I lost them a few times, running into impossible steep granite slabs. Several times I had to retreat and re-find the route, which was no spring picnic, as well. I carefully negotiated my way down off that awful ridge and was faced with the decision of whether to take the easier long way around, or to go back down the more direct way I had come up. Water had become critical for me, as I had finished off the last of my 3 quarts and was chomping on raisens for their energy and water content. Since I knew that the way I had come up wasn't too bad, and that there was probably some nice spring water in the gully I had crossed, I chose the steeper, quicker and shorter route. Fatigue was setting in and almost every downward step resulted in a sharp grunt of complaint. I still had to very carefully control my descent and pay close attention to where each foot landed. This also became a mindgame. I did find some very nice cold spring water and guzzled a quart, then greedily taking another with me for the rest of the descent. When I finally reached the Mist Trail, I was so relieved to be able to walk without peering at the ground ahead. But, this was to be very short-lived.

After a short break at the top of Vernal Falls, I reached a part of the hike that I was dreading. The hundreds of steps of the Mist Trail. The picture below is the uppermost part of the steps.

With aching knees and burning muscles, I took each step one at a time, sometimes favoring my right leg and sidestepping the bigger steps. The sun was setting and I knew I was running a little late. However, there was no rushing to get down off the mountain. The steps seemed endless but, the mist of the falls felt pretty good. As I finally passed the last step, I now had some steep trail to shuffle down, as my tired legs just wouldn't take long strides. I settled into a pace that had me taking tiny steps to keep me from bending my knees too much. When I finally made it down to the flat ground of the Happy Isles, I rejoiced in surviving the epic adventure. It was dark, I was hungry, and home was still more than two hours away. I ended up eating dinner at 11, showered at home at midnight and then called in sick the next morning, with good reason.

One of the most amazing things about this trip was the realization that Ansel Adams took his famous picture with snow on the ground in 1927!

What a stud ole Ansel was!!!

Labels: Diving Board, Half Dome, Mist Trail, Yosemite